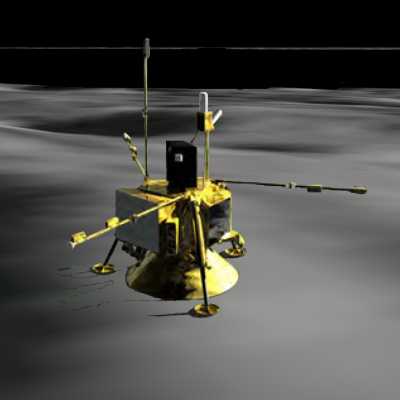

Pictured above rather fancifully (and on-the-fly) is one of a hoped-for three future nodes of the International Lunar Network (ILN) now in the planning stages. This one is situated on the rim of Shackleton crater, near the location of the Moon's South Pole and also within the immense South Pole-Aitken (SPA) impact basin. At an estimated 4 billion years of age, SPA is the largest and oldest known impact basin on the Moon.

Beyond the on-going and highly-anticipated mission of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) are two other "precursor" robotic orbiters considered vital before extended human activity on the Moon can begin. The Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) remains in NASA's budget and is scheduled for launch in May 2012.

Before LADEE the Massachusetts Institute of Technology hopes to use increasing finesse at low-energy lunar transfer trajectories to fly the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission in September 2011. This pair of small orbiters designed to fly in tandem are being developed to improve detail of the Moon's still elusive centers of mass.

Because seismometers left on the Moon during Apollo were clustered around landing sites near the Moon's equatorial latitudes, all on the Near Side, their operation until 1977 left a lot of uncertainty about the precision of their measurements. The differences between the near and far sides of the Moon turned out to be dramatic, especially in elevation and crustal thickness. Scientists now want to co-locate at least two or three seismometers further apart at carefully chosen landing sites to better identify the sources of recorded events. There are some who even believe the source of some moonquake events could be collisions with very high energy cosmic rays. And seismometers are not the only reason for locating ILN nodes at strategic locations on the Moon.

Before LADEE the Massachusetts Institute of Technology hopes to use increasing finesse at low-energy lunar transfer trajectories to fly the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission in September 2011. This pair of small orbiters designed to fly in tandem are being developed to improve detail of the Moon's still elusive centers of mass.

Because seismometers left on the Moon during Apollo were clustered around landing sites near the Moon's equatorial latitudes, all on the Near Side, their operation until 1977 left a lot of uncertainty about the precision of their measurements. The differences between the near and far sides of the Moon turned out to be dramatic, especially in elevation and crustal thickness. Scientists now want to co-locate at least two or three seismometers further apart at carefully chosen landing sites to better identify the sources of recorded events. There are some who even believe the source of some moonquake events could be collisions with very high energy cosmic rays. And seismometers are not the only reason for locating ILN nodes at strategic locations on the Moon.

The only experiment left on the Moon during the Apollo era still in use are the laser reflector arrays at the landing sites of Apollo 11, Apollo 14, Apollo 15 and Luna 21. As the original laser reflector telescope at MacDonald Observatory in Texas was winding down operations last year a new set of instruments continued gearing up at Apache Point in New Mexico. Using laser pulses measurement of the distance to the Moon has gradually improved in precision from 150 cm to slightly above 3 cm. Cosmologists are anxious to improve on what is already an incredibly precise measurement in hope of solving many great questions. Among these is whether or not physical laws as they are known here in the Milky Way are change over great distances.

And that introduction fails even to scratch the surface of why Earth is so fortunate to have a naked Moon located at the same distance from the Sun as itself. And we have not even begun to scratch the surface of the Moon.

And that introduction fails even to scratch the surface of why Earth is so fortunate to have a naked Moon located at the same distance from the Sun as itself. And we have not even begun to scratch the surface of the Moon.

In 1959, almost immediately after the Soviet Union returned the first images of the Moon's far side a very large basin could be seen located almost entirely in the far southern hemisphere. It is now understood that the massive massifs on the south side of the Moon's near side are the rim of the Moon's largest known basin. In latitude, SPA stretches from 200 kilometers this side of the Moon's south pole to 20 degrees south of the equator on the Far Side. It's the largest and oldest known impact basin, at 4 billion years old it predates the more familiar Near Side basins by 200 million years. Beyond it's northern rim are the Moon's highest elevations and, as the Japanese confirmed with Kaguya's laser altimeter the basin holds the Moon's lowest elevations as well.

South Pole Aitken Basin holds the oldest rocks on the Moon and certain unusual traces of elements like Thorium that present question without adequate answers. From the six landing sites of Apollo come traces of nearly all the better-known events that shaped the face of the Moon, except SPA.

At the end of December it was announced that a robotic sample-return mission to "the Moon's South Pole" had become one of three finalists to become a Discovery mission later in the coming decade. But the mission to the Moon presented in the news is not some frivolous, random rock tourist happening. The mission proposed is to land and return samples from the Moon's largest feature, on the Moon's far side and out of direct contact with the ground. Fulfilling such a mission would not just solve mysteries for planetologists, it would be an engineering achievement in robotics, as well.

This is not to say the other missions making the final cut are without merit. Far from it. It's just a fairer representation of the needed science and the programs that are finally already underway to get a firm lasting foothold on the Moon.

South Pole Aitken Basin holds the oldest rocks on the Moon and certain unusual traces of elements like Thorium that present question without adequate answers. From the six landing sites of Apollo come traces of nearly all the better-known events that shaped the face of the Moon, except SPA.

At the end of December it was announced that a robotic sample-return mission to "the Moon's South Pole" had become one of three finalists to become a Discovery mission later in the coming decade. But the mission to the Moon presented in the news is not some frivolous, random rock tourist happening. The mission proposed is to land and return samples from the Moon's largest feature, on the Moon's far side and out of direct contact with the ground. Fulfilling such a mission would not just solve mysteries for planetologists, it would be an engineering achievement in robotics, as well.

This is not to say the other missions making the final cut are without merit. Far from it. It's just a fairer representation of the needed science and the programs that are finally already underway to get a firm lasting foothold on the Moon.

No comments:

Post a Comment